In The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression and Today (OR Books), journalist Jason Boog writes about the plight of writers in the United States since the stock market crash of 2008 and compares their challenges to those of poets, novelists, and journalists in the 1930s. When focusing on the mid-20th century, Boog, the West Coast correspondent for Publishers Weekly, highlights better-known literary figures from the Great Depression (Richard Wright, Cornell Woolrich, Muriel Rukeyser, Nathanael West, Kenneth Fearing) along with more obscure authors (Edward Newhouse, Maxwell Bodenheim, Orrick Johns, Anca Vrbovska).

Boog roots this excellent survey of past and present literary lives in his own experiences as a journalist, one of whose previous employers, a legal publication, went under in 2008. Suddenly without office space, security, or health insurance, Boog perched himself near the American Literature stacks at New York University’s Bobst Library and began an obsessive search for insights into how his predecessors made it through the Great Depression. This quest started with Edward Newhouse’s 1934, novel You Can’t Sleep Here, about an unemployed newspaper reporter who finds himself sleeping in a tent city along Manhattan’s East River, his only showering option in a New York Public Library bathroom. Boog recalls: “A quiet desperation permeated every line of Newhouse’s story. I couldn’t stop reading.” The novel’s protagonist is told that “Anybody who really wants to work can find a job,” an old saw which prompts Boog to note that the claim is as false in the 21 century as it was in the 20th.

Post-2008 internet job boards advertised employment opportunities, but most queries to those ads were answered with automatic e-mail programs which provided nothing concrete. While reading an article describing a thousand people applying for a minimum-wage job at an internet company, Boog was reminded of a 1930s photograph of a throng of despondent men standing listlessly outside an employment agency. The collapse of both print and online outlets for paid writing, which began in the aughts and continues to this day, has left an increasingly diminished market for anyone hoping to cobble together even the most meager living as a word-slinger.

Despite his gloomy prognosis for the future of his trade, Boog is committed to fighting back against the system that eviscerated his industry, and wants his fellow writers to do the same. He argues, “More writers fail than those who ‘succeed,’ and it is how we respond to this failure that defines us in the end.”

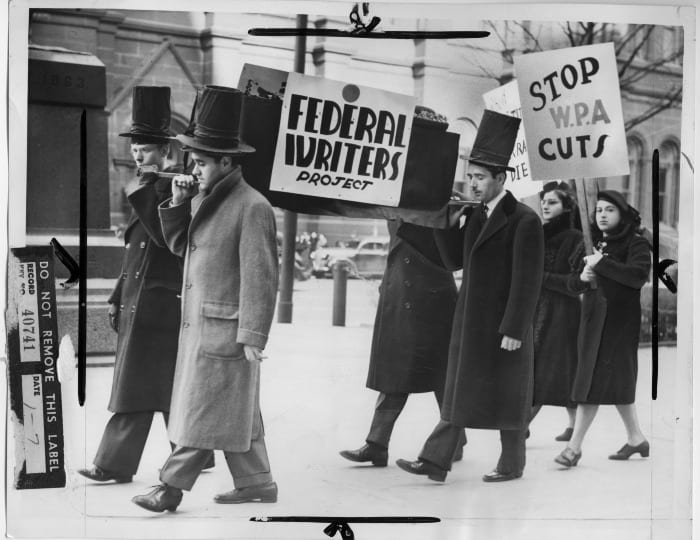

Boog finds inspiration to carry on in the political lives of many ’30s writers. Poet Muriel Rukeyser told a historian the way writers were perceived during the Great Depression: “The public saw them as trash … Living meant going to the office. That meant acceptance, money and the proper capitalist virtues.” Rukeyser eschewed those virtues by joining the radical Writers Union. That organization petitioned President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to include writers among the three-million Americans then being given employment. Their letter to Roosevelt read in part, “800 writers have no work. One of them, in despair, has already committed suicide. We know that you do not intend, Mr. President, that a man is condemned merely because he does not work with his hands.” (The number cited is likely a serious understatement given that one historian counted 1,400 writers listed on New York City relief roles in the mid-1930s.) The Writers Union also stood up to police brutality on picket lines while marching for federal help alongside the League of American Writers, the Authors League, the Newspaper Guild, and the Yiddish Writers Union.

In 1935 Maxwell Bodenheim, whose proletarian poetry appeared in left-wing publications such as the Daily Worker, New Masses, and The Anvil, was so destitute that he appeared at the New York City welfare office with five other Writers Union members and a group of reporters to make a public plea for financial aid. The radical poet’s sit-down meeting with a relief administrator was successful, and Bodenheim’s last-ditch appeal made headlines which inspired more such actions across the country.

Pressure on the U.S. government sparked by writers such as Rukeyser and Bodenheim led to the 1935 launch of the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), which was supervised by the New Deal-financed Works Project Administration (WPA). The tough one-legged poet Orrick Johns, who had survived violent physical attacks while coordinating worker strikes for the Communist Party, was a director of the New York portion of the Writers’ Project for a short time. Johns later wrote of surveying potential recruits: “They were all from the home relief rolls, and it took weeks for some of them to get the habit of clean shirts and pressed trousers. They ran the gamut of mental states, the scared and the stolid, the humble and the proud, reserved and excitable, with a scattering of plain drunks.”

As Roosevelt geared up for the 1936 presidential election, his critics seized on the FWP as an easy target for conservative ire. Right-leaning newspapers attacked a pamphlet that Johns published about New York State; Johns’s supervisor chided him that the publication was “afflicted with the cheapest sort of ballyhoo … Lurid intimations of Chinatown dens, the come-on stuff of the tourist barkers.”

In August 1936 the WPA fired 300 workers. Not all of those who were sacked gave up easily, many initially refusing to leave their workplace. A subsequent demonstration involved 35 unemployed members of the American Writers Union who staged a sit-in at Johns’ office. Johns allowed the protest to proceed without police interference, and resulting publicity forced the WPA to approve the hiring of 50 workers.

Historian David A. Taylor, who chronicled WPA support for writers, noted that the FWP “gave some of the best writers of the twentieth century their first jobs as writers at a critical time,” and “provided an unexpected incubator for talent that was otherwise idled by the Depression.” Among those nurtured by the FWP were Ralph Ellison, who went on to achieve fame with Invisible Man, Claude McKay, a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, and the inventive, hilarious poet Kenneth Fearing.

Fearing’s first collection of poetry, Angel Arms (1929), was a commercial flop, but put him on the literary bohemian map. That partial fame wasn’t enough to keep him out of a booze-soaked rut after the 1929 stock market crash. Emerging from that slump a few years later, he told ace journalist Joseph Mitchell about a political shift in his work: “The thing about these poems is that they express my indignation over such things as that jungle of squatters over on Abingdon Square and people I see … going around the streets at night like prehistoric animals, digging into garbage pails, a sight which epitomizes our so-called civilization.”

Boog contrasts the political engagement of writers in the 1930s with the atomized, depoliticized state of too many 21st-century wordsmiths, concluding that “writers have been surgically removed from the working class.” He notes that in 2002, 10 percent of the publishing workforce had union representation, while by 2012 that number had fallen to 4 percent. The emergence of the tech giants and their “information wants to be free” mantra gave rise to a surplus of “content providers” ready to toil for peanuts or even nothing. Boog writes, “The whole time I struggled to make it as a working writer, I was constantly aware of how many people were willing to do the same work as I was doing and how many of them would write for free.” A lack of class consciousness or solidarity with their struggling peers led aspiring novelists, poets, and journalists to give up whatever advantages they had: “By prioritizing ‘continuing to work’ over taking a stand on pay and conditions, we all contributed to this new reality … I fought bitter battles to hold on to my small corner of the publishing world while trying to ignore the ways in which we are all accountable for the state of the industry in which we work.”

In comparing this century’s tendency toward milquetoast passivity and defeatism with the political consciousness and willingness to engage in class struggle of the ’30s, Boog quotes the journalist Mark I. Pinsky, who wrote, “In the 1930s journalists considered themselves a part of the working class, largely identified with the political left, and understood the power of collective action. In the post-Watergate era, journalists became white collar, college-educated, and middle class, often upper-middle class. And so, they were unable to slow, and thus cushion, the inevitable decline of newspapers.” Boog sees the same problem in the highbrow world of literary fiction and poetry. He observes that “If writers have not identified with workers since Nixon, then we hardly have any hope of saving ourselves again with any sort of labor organization … Someday soon, the only remaining ‘working’ writers could be people who can afford to support themselves through grants, other work, or an inheritance.”

But as Boog’s narrative cuts back and forth between the Great Depression and the post-2008 recession, his book includes hopeful signs from our present era. For instance, he connects the 1930s Greenwich Village-based Raven Poetry Circle, whose members posted poems on a fence in Washington Square Park, to Occupy Wall Street’s poet-participants, who were equally enamored of free verse with an anti-capitalist bent. In 2011, Occupy started an Occupy Wall Street Poetry Anthology, which reminds Boog of the Raven Circle’s poetry anthology. The Occupy collection included contributions from such well-known talents as Adrienne Rich, Michael McClure, and Eileen Myles. Occupy Wall Street librarians, who had built a library in Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park which boasted a collection of 8,000 titles, wrote of the anthology’s importance, “Poetry illuminates the soul of Occupy Wall Street. … This occupation is about transforming consciousness and the poetry community is a major part of that process.

As he finished writing The Deep End, Boog commuted daily through Los Angeles and saw the sorts of homeless encampments now found in any big U.S. city, the sorts of “Hoovervilles” which Edward Newhouse wrote about. Boog remarks, “These encampments are symptoms of a disease we don’t want to acknowledge. We pretend they aren’t there until we can’t pretend anymore. We can feel this global economic rot creeping all around us, but things won’t change until a writer like Newhouse forces us to see things the way they really are.”

Boog begins The Deep End with an introduction praising the Green New Deal, a legislative response to the climate-change crisis which was developed via collaboration between environmental and social justice movements and progressive members of Congress including Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-New York) and Senator Edward Markey (D-Massachusetts). That “moon shot” project is inspired in part by the New Deal of the 1930s, which helped so many of Boog’s literary heroes survive. It provides Boog with much-needed hope for the future, and he also emphasizes the need for a Green New Deal in the book’s conclusion.

The Deep End ends with the nightmare combination of COVID-19 and the kleptocratic reign of Donald J. Trump. Although that toxic stew can feel unbearably grim, Boog sees potential for great changes with the emergence of the youth-led climate justice group the Sunrise Movement. Begun in 2017, Sunrise is now forging ahead with the sorts of online organizing that are essential in a time of shelter-in-place lockdowns. They are moving forward, as should we all, in the spirit of Boog’s exhortation that “If we only hold on to one lesson of the Crisis Generation [of the 1930s], let’s remember this one: they did not surrender.”