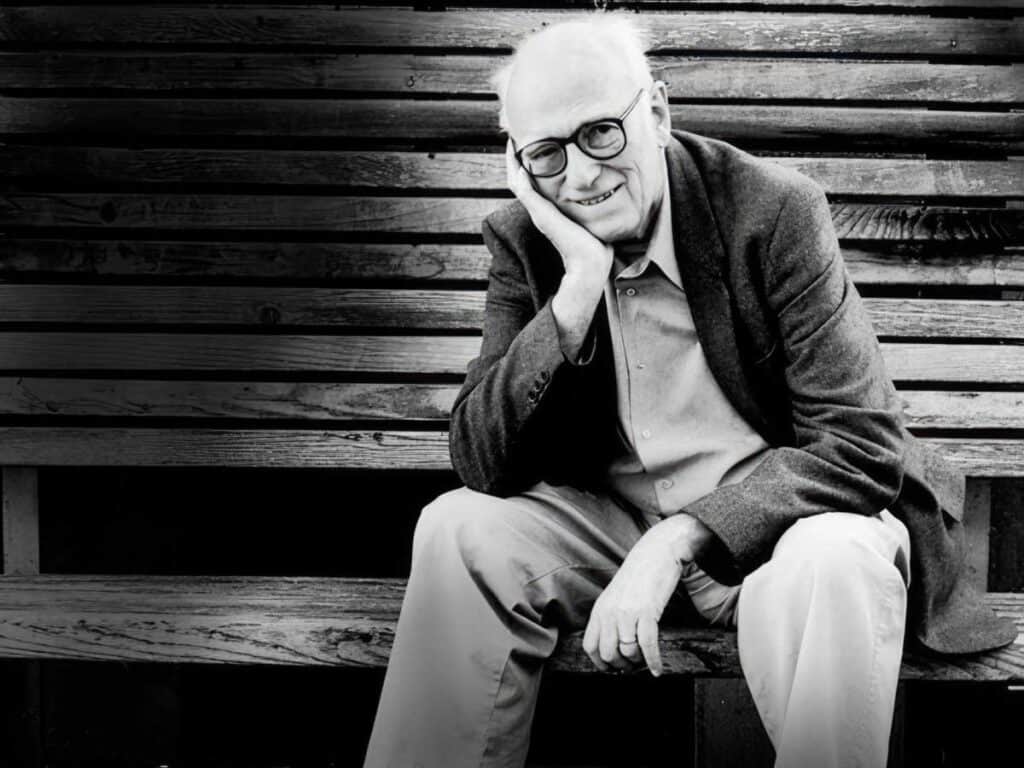

The remarkable crime fiction writer Donald E. Westlake (1933-2008) had an impressive career encompassing short stories, a wide variety of stand-alone novels, and several sets of series books. His two most famous recurring protagonists, John Dortmunder and Parker, written under the pseudonym Richard Stark, appeared in several film adaptations; a few movies have also been made from some of Westlake’s non-series work. Throughout his prolific career, Westlake kept a low profile, inexplicably never achieving a best-seller.

When it comes to compulsively readable and wildly entertaining crime fiction, few authors can touch Westlake’s work. He was as much appreciated by his fellow writers as his readers: Westlake’s friend Lawrence Block wrote that his colleague “[has] never written a bad sentence, a clumsy paragraph, or a dull page.” Westlake won Edgar Awards in three different categories, and was voted a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America.

Westlake also wrote numerous screenplays and teleplays, many them never produced, and he sold the rights for at least ten books that were never made into movies. While he never got rich from his Hollywood sales, he did make far more money from the film industry then he did from writing books. In the late 1990s Westlake wrote, “From time to time I’d be hired to write a screenplay about something or other. The movie industry needs writers, but ignores writers as a matter of principle; it is the perfect place for a writer who didn’t want to be noticed.” Westlake didn’t want high visibility because “I wanted to write whatever came into my head, and not worry about it.”

The Richard Stark books live up to that pen name (the first name came from Richard Widmark, a favorite of Westlake’s). They are stripped-down, high adrenaline stories that deliver pure action with plenty of satisfying plot twists. These novels are admired by other crime writers–Dennis Lehane called Parker “the greatest antihero in American noir”–as well as more rarefied types–Booker Prize winner John Banville called the Parker books “… among the most poised and polished fictions of their time and, in fact, of any time.”

Other than in one novel in which he goes to jail, the thief Parker never gets caught, and despite complications, he usually walks off with the money. Westlake wrote that “Parker is a depression character, Dillinger mythologized into a machine.” These narratives definitely lean toward the noir end of the spectrum, though sticklers might argue that hard-boiled would be a more appropriate descriptor. Author Jack Bludis was quoted in Noir City magazine as saying, “hardboiled = tough, noir = screwed.” By that definition the Parker books could fit into either category: Parker is plenty tough, but the people who cross him are definitely screwed. Westlake himself said in a 2006 interview, “I think hard-boiled and noir are both a little past their sell-by date. Hard-boiled is what the [WW2] vets brought back with them, and noir is the world they found when they came home. I think hard-boiled is still possible, but noir today is another word for artsy.”

In 1966 Jean-Luc Godard shot Made in the USA, which the director claimed was based on The Jugger, a 1965 Richard Stark novel the film’s producer didn’t actually have the rights to. Godard’s film was made on the fly and seems to have been mostly an excuse to show off Anna Karina playing with a gun in various brightly-colored outfits. In 1967 film critic Gilles Jacob wrote that in Made in the USA Godard “has managed to disincarnate the object,” which is slightly more comprehensible than most of the film’s dialog. Godard’s Breathless and Alphaville both worked as, among other things, an oddball aesthete’s tribute to U.S. crime novels and films. But Made in the USA is just a pretentious mess. The film does include a radiant Marianne Faithful singing “As Tears Go By,” which doesn’t particularly fit into what passes for a story but which does make a strong impression.

The first noteworthy adaptation of a Westlake book was Point Blank (1967), based on the first Parker book, The Hunter (1962). The Hunter‘s opening sentence sets the tone: “When a fresh-faced guy in a Chevy offered him a lift, Parker told him to go to hell.” The anti-hero tough guy then lights his last cigarette and walks across the George Washington Bridge. Parker is broke, after being left for dead by his wife and an accomplice in their stickup of international arms smugglers. Scraping together a stake by pulling petty scams, Parker is driven by an all-consuming desire for revenge. After tracking down his wife, he tells her what he will do to his former partner in crime Mal: “I’m going to drink his blood. I’m going to chew up his heart and spit it into the gutter for the dogs to raise a leg at. I’m going to peel the skin off him and rip out his veins and hang him with them.”

When Parker does get his hands on Mal, though, Parker’s anger is not satisfied. “Mal wasn’t enough, he was easy, he was too easy, he was the easiest thing that ever happened.” Mal also doesn’t have the share of the robbery he stole from Parker, since he used it to pay off a debt to the Outfit, a Mafia-like organized crime network. So after dispatching Mal, Parker moves on to target Outfit operatives.

Westlake told an interviewer that he didn’t do anything to make Parker “reader-friendly.” This one-man force of nature has no use for small talk or patience with anyone he feels is wasting his time. He gets no pleasure from killing, but won’t shy away from it if he decides that it is his best option; unlike in the film adaptations of The Hunter, in the novel Parker planned to kill Mal before Mal beat him to the punch, because he saw Mal as a coward and a “weak link.” As Westlake noted, “[There is] no socially redeeming quality in this guy at all.”

In Point Blank, Parker becomes Walker, who Lee Marvin plays with unrelenting ferocity. Critic Luc Sante wrote that Point Blank “takes major liberties with the plot but brings out the latent modernism of the series. It is all noon light and harsh edges, in striking contrast to the shadows and melancholy of film noir.” The film was director John Boorman’s first major feature after helming the Dave Clark Five vehicle Having a Wild Weekend, and the British filmmaker went all out with elaborate cutting, multiple flashbacks, and a variety of striking visual touches. Cinematographer Philip Lathrop worked seamlessly with Boorman to shoot each scene in a specific color.

At Lee Marvin’s insistence, Boorman had final cut on the film. Boorman later said in a DVD commentary that Marvin agreed to do the project if they threw out the existing script, and, in Boorman’s words, “we went back to the book, of course.” But in an interview with author Michel Ciment, Boorman said, “You know, I’ve never read the book!” Certainly the original script, by David and Rafe Newhouse, was much closer to The Hunter. The final screenplay is credited to Alexander Jacobs and the Newhouses.

Point Blank changed locations from its source material and added characters, including a memorable Angie Dickinson as a quasi-love interest who moves quickly from bashing Walker on the head with a pool cue to lustily climbing all over him. But the film successfully captured Parker’s unstoppable mission, whose sole purpose can be summed up in four frequently repeated words: “I want my money.” Marvin, who Boorman called “a master of gestures” and “very intuitive,” is entirely convincing as Walker. It’s one of his best performances, one of the reasons the film still holds up well after repeated viewings.

The more recent adaptation of The Hunter is, to say the least, far more predictable. Though it follows The Hunter more closely than Point Blank, the Mel Gibson vehicle Payback (1999) is underwhelming at best. Suffice it to say that if you’re not a Mel Gibson fan, the film is quite skippable.

The Outfit (1973), based on a Stark novel of the same name, stars Robert Duvall as the Parker stand-in Earl Macklin. Macklin is released from prison in the film’s opening sequence, shot in an actual correctional facility. Bett Harrow (Karen Black) who is waiting to drive him to freedom, tells Macklin that his brother has been gunned down in retribution for the brothers robbing an Outfit-controlled bank. Macklin recruits his old buddy Jack Cody (Joe Don Baker) to wage a full-scale assault on the Outfit’s operations, starting with a card game where Macklin takes on Menner (played to perfection by the great Timothy Carey). From there the mayhem continues until the entire organization is brought to its knees.

No character like Cody appeared in Westlake’s novel; in the book Parker unleashes a network of freelance heisters instead of going at his adversaries with only Cody and Bett. There are other differences between the book and the movie, but overall director John Flynn and cinematographer Bruce Surtees manage to remain faithful to the book’s tone, with its largely rural locations providing a nice relief from run-of-the-mill urban Hollywood crime fare. The one sour note comes in an unfortunate scene where Macklin engages in stereotypical and entirely unnecessary prolonged slapping of Bett.

Westlake judged The Outfit to be “quite good,” telling an interviewer “It is a … small movie with every B-movie actor you’ve ever thought of in it.” The cast is indeed rich in veteran character actors, including Elisha Cook, Jr., Marie Windsor, Jane Greer, Henry Jones, Richard Jaeckel, and, most indelibly, Robert Ryan as the mob boss Mailer. Anita O’Day even has a cameo singing in a deserted club.

Director Taylor Hackford’s 2013 film Parker, mostly based on Flashfire (2000), is a diverting entertainment which doesn’t ascend to the giddy heights of Point Blank or equal the stripped-down momentum of The Outfit. Working from a script by John McLaughlin, Hackford opens the film with a robbery at the Ohio State Fair that is exciting and visually impressive. It’s also much more of an elaborate undertaking than the opening bank robbery in Flashfire.

After the changed beginning, McLaughlin’s screenplay mostly follows the book, from the opening betrayal of Parker by his crew to the final campaign of Parker’s retribution. Though it takes a bit getting used to Parker having a British accent, Jason Statham is suitably cool and unstoppable in the title role. He’s not Lee Marvin or Robert Duvall, but then he isn’t as awful as some critics implied (especially the ever-catty Rex Reed, who wrote, “Mr. Statham is to acting what Taco Bell is to nutrition”). He’s certainly more appropriate for the part than Mel Gibson. The worst part of Statham’s performance is his unfortunate attempt at a Southern accent when Parker impersonates a wealthy Texan scouting for Florida real estate.

In Flashfire, the real estate agent Leslie Rogers is described as “a round-faced blonde” who is “one of an interchangeable half dozen of such women” in her “spacious cool office.” Not exactly the famously heart-stopping Jennifer Lopez, who plays her in the film. The sexual chemistry between Leslie and the typically-disinterested Parker is non-existent in the book, while in the movie Statham and Lopez share a mutual attraction and even kiss briefly. Statham’s Parker is also more noble than in the book; in Parker‘s opening robbery Statham announces to a roomful of civilians he is holding at gunpoint, “I don’t steal from people who can’t afford it, and I don’t hurt people who don’t deserve it.”

Flashfire is one of the Stark books in which Parker’s lover Claire appears. Claire mostly serves as a backup to help Parker out of jams, and in Flashfire she remains at a distance from the main action. She’s not a hardened moll, but a woman with her own life who doesn’t want to know too much about Parker’s work. In Parker, Claire, played by Emma Booth, is a nurturing presence who shows up to tend to Parker’s wounds while Leslie looks on enviously. Booth’s character is young and more than a little vapid, which makes Parker’s loyalty to her in spite of Ms. Lopez’s readiness for romance highly improbable.

The main difference between the film The Split (1968) and the novel The Seventh (1966) is that the movie’s protagonist is black. Though Westlake wrote few African-American characters, much of his ’60s fan mail came from young black men who enjoyed reading about the exploits of an outsider looting establishment institutions. The casting of the lead was a brilliant stroke: Jim Brown, former NFL superstar, plays Parker surrogate McClain. Who better to rob a football stadium while a game is being played than a former pro? Brown brings new meaning to the word “hulking” and box office revenue was undoubtedly increased by the extremely cool actor repeatedly taking his shirt off.

Jim Brown is joined onscreen by an impressive roster of 1960s-’70s movie actors, including Ernest Borgnine, Donald Sutherland, Warren Oates, Jack Klugman, and Gene Hackman. Gordon Flemyng isn’t an especially memorable director (he worked mostly in TV) but Burnett Guffey’s cinematography is first rate. Visually, this vehicle very much a 1968 period piece, with sharp outfits and what passed for hip dialog in Hollywood at that time. But the screenplay, aside from the actual robbery, the highlight of the movie, makes a hash of Westlake’s book. It’s easy to see why Westlake had nothing positive to say about this cinematic outing, which is probably best only viewed for cheap laughs or for Ernest Borgnine’s loud suits, not that those two things are mutually exclusive.

At the other end of the spectrum of Stark/Parker adaptations sits Mis a sac (1967; English title: Pillaged), a very faithful adaptation of The Score. This caper movie focuses on a heist Parker (here called Georges and played by Michel Constantin) helps plan wherein a crew of men lay siege to an entire town’s safety deposit boxes and vaults. In the book Parker reflects that “it was just too big and fantastic an idea to begin with, it was science fiction,” but in both book and film the size of the haul quickly lures him in.

The body count in Mis a sac is lower than in The Score. The other major difference between the two is that in the end of one crime pays, whereas in the ending of the other it doesn’t. But the film gets the feel of the book just right. The pros on the job all have the look and attitude of veteran criminals, with enough differences between them to keep things interesting. As always with Westlake’s books, the plotting of The Score is seamless, and the story hurtles along like a freight train, a force of pure narrative drive. That meticulously choreographed momentum also drives Mis a sac, and makes it a classic of French gangster cinema.

Mis a sac fully deserves to get the deluxe Criterion re-issue treatment. Unfortunately, the only version available to those requiring English subtitles is a poor dupe of a video.

Le Couperet (2005) is another great French crime film deserving of a Stateside DVD release. Adapted from the stand-alone Westlake novel The Ax (1997), it was directed by Costa-Gavras, best known for the brilliant political thrillers Z, State of Siege, and Missing, and produced by Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, the writers and directors of such cutting-edge European art house fare as Two Days, One Night and La Promesse.

Le Couperet is beautifully shot and edited, with compositions and camera movements that make it equal to the other work of Costa-Gavras and the Dardenne Brothers. It stars a convincing Jose Garcia as Bruno Davert (in the book this protagonist is named Burke Devore), an accomplished paper company manager who is discharged in a round of corporate downsizing, a phenomenon still in its first wave when Westlake wrote The Ax.

In Westlake’s novel, Devore observes that he is a casualty of a “… kind of business management that has never been seen in the world before, trashing productive people from productive careers in productive companies.” After several years of interminable, unsuccessful job interviews, our anti-hero decides to take desperate measures. Though Devore is well aware that his real enemies are the prosperous few far up the corporate food chain, he comes to the conclusion that the only way he will re-enter his old field is to kill off the competition for the few available jobs. Devore explains, “I’m not a killer. I’m not a murderer, I never was, I don’t want to be such a thing, soulless and ruthless and empty. That’s not me. What I’m doing now I was forced into, by the logic of events; the shareholders’ logic, and the executives’ logic, and the logic of the workforce … ” Le Couperet‘s screenplay sticks close to The Ax, the principle difference being a nicely warped final twist that is added to the movie.

Westlake’s screenplay for The Stepfather (1987) is even darker than The Ax. It is based on the true story of a man who murdered his entire family then disappeared, only to be tracked down years later.

Describing his experience on the film, Westlake told an interviewer, “ … there were some changes, but that’s about ninety percent [my script]. That’s amazing in the movies. That never happens (…) it’ll never happen again. But I got it the once.”

Given the propensity of movie stars to insist on script changes,Westlake was fortunate that no big-name actors wanted the lead role of unbalanced family man Jerry Blake. The final choice to play the title character was Terry O’Quinn, a then little-known actor who went on to success on the TV show Lost. Westlake said of O’Quinn, “Oh, God, is he good.” The film’s director Joseph Ruben also had nothing but good things to say about O’Quinn: in the DVD commentary for the film Ruben describes O’Quinn as a consummate professional who “just does it … [he] wasn’t the kind of actor who needs long conversations about his childhood.” O’Quinn handles the transitions from a corny, sentimental suburban husband and father to an unhinged psychopath with aplomb, hitting every note perfectly in a superbly nuanced performance.

Jerry Blake is a real estate salesman with a big American flag in his yard who tells a group of neighbors, “Sometimes I truly believe that what I sell is the American Dream.” He strives to be as wholesome as humanly possible, but he has trouble accommodating family members with minds of their own, especially his stepdaughter Stephanie, who senses his dark side. His obsession with creating a perfect family is clearly impossible, which makes it hard for him to maintain his equilibrium for long. Soon bad things happen, with a vengeance.

Ruben described Westlake as “a classic pro on every level.” The director appreciated how quickly Westlake agreed to delete the killer’s childhood flashbacks, which were included in an early version of the script; O’Quinn’s portrayal of the monstrous stepfather is even scarier without a detailed backstory. Jerry’s few indirect lines about surviving difficult times are enough. When his new wife Susan (Shelly Hack) asks about his past, Jerry says “it isn’t real, it’s just a dream (…) the only reality is this moment.” This line echoes countless ridiculous cliches from mainstream Hollywood love scenes, but it’s a perfect Westlake wrinkle that the person saying it is an insane lunatic who wiped out his previous family. As Ruben notes, the movie is “a very dark comedy.”

Westlake’s two best screenplays were for The Stepfather and The Grifters (1990). They were also his two best experiences in Hollywood. Stephen Frears, director of The Grifters, invited Westlake to be on the set, which the writer appreciated. Westlake later explained in an interview, “It was so nice to be in a boat in which everybody was rowing in the same direction instead of getting hit in the head with a lot of oars.”

Initially Westlake thought Jim Thompson’s novel, also titled The Grifters (1963), was too bleak and passed on Frears’s request that he write a screenplay. But once he committed himself to the project, Westlake worked hard to remain true to Thompson’s pitch-black vision. When producer Martin Scorsese asked Westlake how the writing was going, Westlake replied, “I’m doing damage on every page.” His script is extremely faithful to Thompson’s novel, including the book’s startling ending, which Westlake insisted remain intact. The three leads, Anjelica Huston, John Cusack, and Annette Benning, all fought for inclusion of Thompson’s dialog; Westlake later noted, “ … it’s nice that they were defending the writer. Everybody had this feeling that we were doing something good.

Westlake created a brilliant opening which placed the three main characters, Roy Dillon (Cusack), his mother Lily (Huston), and the seductive hustler Myra Langtry (Benning), on an equal footing. The three leads appear in a triptych, each of them walking purposefully in what Thompson biographer Robert Polito called “a dazzling bit of invention” which “I think [Thompson] would have loved.”

In addition to having a gift for very dark material, Westlake was a brilliant comic writer. Even in his darkest stories, he can be extremely funny in a wonderfully off-kilter fashion. He doesn’t go for predictable sit-com humor, but with single-talent characters trying to make a larcenous living with minimal skills, unpredictable situations build toward comic outcomes. Through a series of hilarious novels the bumbling thief John Dortmunder manages to make every mistake that Parker avoids: he misjudges people, they get the drop on him, he fumbles on his follow-through. Dortmunder rarely gets away with any proceeds from his criminal endeavors, and Murphy’s Law is a constant.

Though Robert Redford might have been an odd choice to play Dortmunder, The Hot Rock (1972), adapted from a Westlake novel of the same name, is a very entertaining caper movie. It’s full of great comic actors, primarily Ron Leibman as Murch, the gearhead driver of Dortmunder’s crew, and Zero Mostel as an uncle of one of Dortmunder’s accomplices. Aside from the addition of Mostel’s character and a change in the ending, the movie follows the book closely. Westlake liked the film and called William Goldman,who scripted The Hot Rock, “the best living screenwriter.”

Westlake’s next novel after The Hot Rock was another Dortmunder book, Bank Shot, which he sold the film rights to before the book was even published. The movie version, also called Bank Shot (1974), featured George C. Scott as the Dortmunder-like lead. Critic Terrence Rafferty spoke for many when he called the movie “absolutely dreadful.” Suffice it to say that Westlake was not a fan.

One last film worth noting is Cops and Robbers, which Westlake scripted. Westlake also wrote a book of the same name after the film was made; in the author’s words, “I did the screenplay first, so that became a kind of extended outline for the novel, and I could put into the novel what I wished the actors had done. But generally I think the writer of the book is going to try to keep in things he loved in the book that are wrong for the movie.”

Cops and Robbers has two excellent lead actors in Cliff Gorman and Joseph Bologna, playing frazzled cops who decide to pull a major heist to finance their early retirement. Bologna later described Westlake as “a super guy” who “embraced my ideas for the character.” The actor also recalled, “This movie was plain joy, it was fun every day to go to work.” John Ryan is also excellent as a mafioso who Gorman and Bologna arrange to sell millions in stolen securities. His character is all lethal arrogance, a formidable opponent whom the two protagonists almost don’t vanquish.

The other major reason to watch the movie is New York City circa 1973, where the film was shot on location. For anyone who wonders what the borough of Manhattan looked like before Wall Street and Walt Disney transformed it into the upscale, spic and span island it is today, look no further.

Westlake produced clear, concise writing that didn’t employ fancy flourishes to make points; unlike too many authors, his published work never cried out for editing. As varied as the films made from his books are, Westlake’s own work is of consistently high quality. He was a consummate professional who wrote unpretentious, wildly entertaining short stories and novels that always delivered the goods. His writing is smart without being pompous or smug, and funny without being patronizing.

It’s a shame that his dark comic mind isn’t still with us to skewer the forces behind our current national malaise. In lieu of that, we can always go back to his classic 1996 romp What’s the Worst That Could Happen, which features a sleazy billionaire real estate developer and casino owner named Max Fairbanks, who John Dortmunder subjects to repeated retaliatory robberies after Fairbanks lifts Dortmunder’s good luck ring in the book’s opening. As the crass, greedy, narcissistic Fairbanks gets his just desserts over and over, who could help imagine the same thing happening to a present-day crass, greedy, narcissistic real estate mogul who is just begging for the same treatment?